When Matthew Perry died in October 2023, my first thought was about my teenage son. I knew he’d hear about it—through friends, on social media—because he, like so many teens, is a Friends fan. And if you’ve ever watched the show, you know that Perry’s Chandler Bing wasn’t just a character. He felt like… a friend. A really good friend.

Yet, in our home, we didn’t talk much about Perry’s death. At first, there weren’t many facts about what had happened. Though I followed the puzzling news stories, my son didn’t ask questions, so I didn’t wade in.

But now, more than a year later, Perry’s story is back in the news. Two of the five people accused of supplying him with illicit ketamine are about to stand trial in California. And investigators have since uncovered more details about what happened in the days leading up to his death.

So now feels like the right time to have that conversation with my teen.

Perry’s story is complex

At first, I thought I could explain what happened in a simple way. But I quickly realized that talking about Perry’s life and death—especially with a teenager—required more research, understanding, and nuance.

To have an informed conversation with my son, I listened to the audiobook of Perry’s memoir, learned as much as I could about ketamine, and followed the investigations into those who enabled his drug use before his death.

I’m sharing what I learned here, in the hope that it helps you talk about Perry’s story with the teens and young adults in your life.

Why talk about a celebrity’s death?

Perry wanted his legacy to be about helping others understand addiction—not as a moral failing or a lack of willpower, but as something complex, persistent, and deeply human.

For parents, his story offers an opportunity to start a meaningful conversation about substance use, addiction, and harm reduction. Especially if you and your children don’t have any personal stories to discuss, a celebrity story can be a way in.

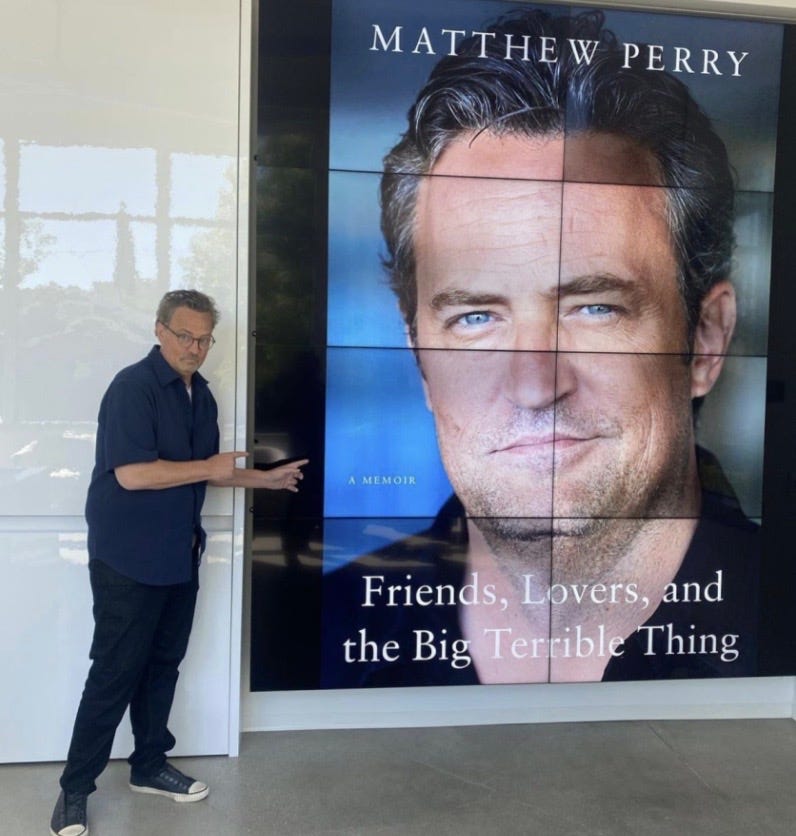

And Perry was open about his struggles. In his memoir, Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing, he didn’t shy away from the hardest parts of his addiction, even when they cast him in a negative light. He gave us the gift of talking about it publicly—something not everyone has the privilege to do—because addiction remains so deeply stigmatized.

But even if Perry wanted us to talk about addiction, don’t be surprised if your teen resists the conversation. They might say, "I don’t do drugs, and I don’t plan to, so why does this matter?"

That resistance is natural. But like sex education, these conversations aren’t just about personal choices—they’re about preparation. Even if it feels uncomfortable, it’s still your role as a parent to guide them through difficult topics.

REMEMBER: This doesn’t have to be one big conversation. It can be a series of smaller talks, spread out over time. Frequent, informal discussions about substance use are far more effective than one long lecture.

ASK: “What do you know about Matthew Perry? Have you heard anything about how he died?”

Let them share what they’ve heard before you start filling in the gaps. Resist the urge to jump in with corrections right away.

What happened to Matthew Perry?

Perry’s death is a tragic example of how it’s not always the substance itself that is fatally harmful—but rather, how it is used.

In his final days, Perry was using ketamine in two different ways:

In therapy, under medical supervision.

At home, unsupervised, with illicitly obtained ketamine.

It was the at-home use that put him at risk. He was reportedly using ketamine up to eight times a day. On the last day of his life, he used it three times. In his final hours, he instructed his assistant in a text to “shoot me up with a big one.” He also asked his assistant to prepare his hot tub for use.

After administering that dose by injection, his assistant left Perry at home alone and went to run some errands. When he returned, Perry was face down in the hot tub. He had drowned.

The risks beyond overdose

Perry didn’t technically die of an overdose—he died from using a large amount of ketamine and then getting into a hot tub. That distinction matters. Teens need to understand that context is just as important as chemistry when it comes to substance risks.

Unlike opioids, which can directly suppress breathing and cause fatal overdoses, ketamine does not typically cause death from overdose in the same way. Instead, the dangers of ketamine are more often related to impaired consciousness, risky behaviours, and environmental factors.

Ask: "Ketamine is used as both a mental health treatment and a party drug. What do you think makes the same substance “safe” in one setting and risky in another?"

Explain: Even legal, prescribed drugs can be dangerous when mixed with other substances or used in risky environments.

Hot tubs can cause overheating, dehydration, and unconsciousness—which can be deadly if someone is under the influence.

Being alone while using a substance can be especially dangerous, as no one is there to help if something goes wrong.

Addiction doesn’t discriminate

Perry wasn’t someone who lacked resources. He was rich. Famous. He had access to the best doctors, the best treatment, the best support money could buy.

Yet, substance use shaped his life from his teens to his 50s. His memoir describes years of struggle—sometimes he was sober, sometimes he wasn’t. At the time of writing, he had been in recovery. And still, he reported that many of the rehab programs he tried didn’t really help, and he relapsed many times.

Many people still believe addiction only happens to those who lack willpower or who make bad choices. But Perry’s story proves otherwise.

ASK: "Do you think people understand the difference between using substances occasionally, relying on them regularly, and becoming addicted? How do you think someone knows when they’ve crossed a line?"

Conversations like this move beyond the outdated “drugs will ruin your life” messaging and into something that actually gives teens the knowledge to navigate real-world situations. Even if they never use substances themselves, they will encounter people who do.

EXPLAIN: Addiction is complicated. Even when someone seems to be in recovery, they can relapse. Some people struggle to stop more than others, and even doctors don’t fully understand why.

End with compassion and action

Perry wanted his story to help people. We can honour that by using it to educate—not to shame or scare.

ASK: "If you or a friend were struggling, what do you think would help?"

Let them take the lead. Give them space to think critically. Keep the door open for future conversations.

EXPLAIN: Remind your teen that while you hope they don’t use addictive substances, you believe people struggling with addiction deserve love and compassion—not judgment.

Connection is the whole point

In the end of his memoir, Perry wrote about his deep desire for connection. What he wanted most, he said, was love and attention—especially from his parents.

That part broke my heart. It reminded me that what matters most in parenting isn’t having all the “right” answers—it’s simply making the effort to connect.

Could you be any more supportive?

Your teen doesn’t have to be using substances for these conversations to matter. They might one day have a friend who struggles with addiction, or they might be in a situation where they have to make a quick decision about their own safety.

Talking about drugs isn't lecturing—it's equipping young people with knowledge, critical thinking, and the confidence to make informed choices.

If you’ve got a Friends-loving teen at home, chances are they’ve echoed Chandler Bing’s iconic catchphrase: "Could you be any more… [insert sarcasm here]?" For those who didn’t watch the show, Perry’s character was known for his dry humour and exaggerated way of emphasizing words, making this phrase one of his most famous comedic quirks.

So next time they groan, “Could you talk about drugs any more?”—just smile and say, “Yes, actually. Because I really care about you.”

Yes it's tragic but he had a worthwhile career and beat up Justin Trudeau